I was playing around with a popular app on my phone one day. It was called FaceApp, and I was cracking up at all of the silly filters showing what it would look like if I had long hair (or any hair at all, for that matter).

Then I found the application’s “our son” filter and was intrigued. I remember years ago howling with laughter watching the popular recurring Late Night with Conan O’Brien TV segment called “if they mated,” and I wondered if this filter would do essentially the same thing.

It did, only the results weren’t exactly what I expected. I uploaded a photo of my wife Kat, paired it with a photo of myself, pressed the filter and waited for the results. My wife and I do not have children, so I was curious about what I would see.

What would it be? A monstrous creature with buck teeth and a huge unibrow? Or maybe a horse-faced bug-eyed dumbass with a forehead big enough to land a plane on? All taking after myself, of course. This was surely going to be epic.

After a few moments, the AI-powered algorithm displayed its output. I held the phone closer to my eyes to make sure I was seeing correctly.

Staring back at me was a familiar face. It was my nephew … only it wasn’t my nephew.

It was … our son!

I was fascinated. I had been expecting a hilarious outcome like I’d seen on Conan’s TV show, but instead, I was looking at a sincere programming effort to show what a child of ours might really look like.

I quickly tried the “our kids” filter, and I marveled as it displayed a photo of an adorable little girl as well — a face that seemed to bear a small resemblance to my sister as a child. This app was so strange and wonderful.

I eventually exhausted all of its funky filters and stopped using the app. I think I had moved on to another app called Reface that lets you do intelligent things like put your head on Kim Kardashian’s body.

I may have tried it, okay? You know, for science.

Recently I had a thought that perhaps I could use FaceApp for more than just hijinks. What if I could use it to create a photo of one of my ancestors?

First, a little backstory.

My great-great-grandfather Henry Laker died in 1912 in a tragic hunting accident. My family has never seen a photo of this man.

We’ve reached out to distant relatives to see if perhaps they had one, but we’ve never had any luck.

Then in 2012, I met some cousins in Indianapolis who were descendants of Henry’s younger brother, Joseph.

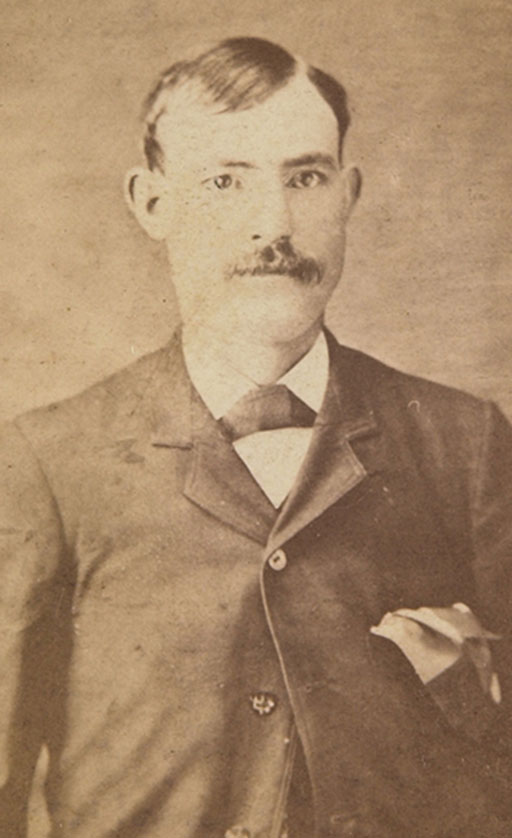

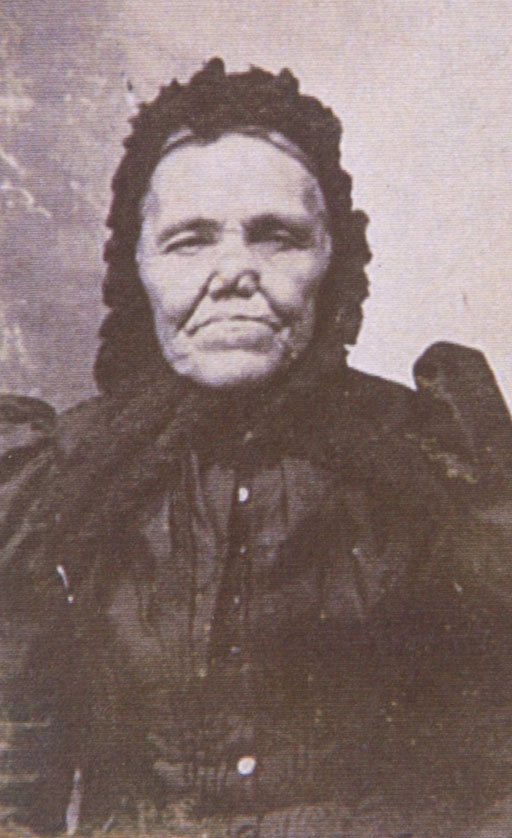

Although they didn’t have a photo of Henry, they did have something almost as good: They had several pictures of Henry’s brother as well as both of his parents! These were very exciting finds as we had not seen photos of these long lost relatives either.

I never thought I would ever see the face of my immigrant ancestors, and there was something so satisfying about “meeting” them at last.

Ploogenheinick

Years went by, and it began to gnaw at me again that we didn’t have a picture of Henry. What did he look like? Did he resemble his brother Joseph? Did one of his sons favor him?

I tracked down another distant relative in Indianapolis who was descended from my ancestor’s sister. I believe that Henry and his sister were close, and I thought it might be possible this family would have a picture.

I sent the family a photo I had of their ancestor along with a letter. I never heard back, and I began to feel sad as I slowly accepted the reality that I probably would never see this man’s face.

I don’t know why it felt important to me, anyway. Most people don’t worry about such things. But I do. Such is my curse.

One day it hit me: Why not use FaceApp to create an “our son” image from the photos of Henry’s parents? Is that crazy? Maybe.

But I figured it couldn’t hurt to try. So I dug into my digital archive in search of the old photos.

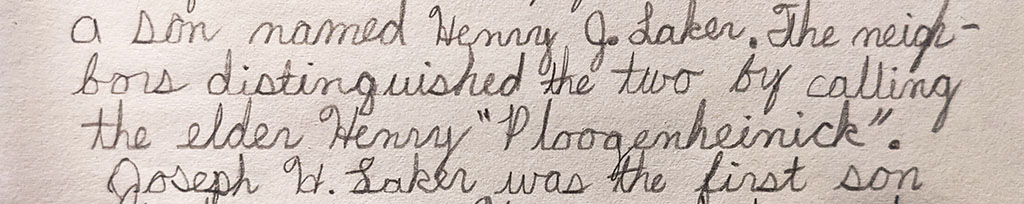

While searching I remembered a story about my family that had been passed down through the generations. Henry’s father was also named Henry, and the two men were so often confused in conversation that neighbors came up with a “Spitzname” for the older man: Ploogenheinick.

This information originally came from Carl Laker, my second cousin three times removed, as told to my mother in the 1980s. She wrote it down as “Ploogenheinick,” and for years we never knew what it meant other than a silly-sounding name.

One day while speaking with a German friend, I asked his thoughts on the meaning of the name. He told me it made no sense in German, but he did offer the opinion that it was a phonetic spelling.

“Pflügen means to plow,” he said. He did not know the man’s real name was Henry. Once I told him that bit of information, we both agreed that it was quite possible the neighbors were using the man’s name as it would have been used in Germany: Heinrich. However, the pronunciation of the “ch” in German has a softer sound than in English, so it is also possible they were using the pet name for Henry, which is Hank in English or sometimes Henck in German.

If it truly was a phonetic spelling, then it’s possible the correct spelling was actually “Pflügenheinrich” — literally “Plowing Henry.”

Mom may have added an extra syllable as she wrote it down, or perhaps she copied verbatim the way Carl had written it, but no one really knows for certain. There is one competing explanation, however.

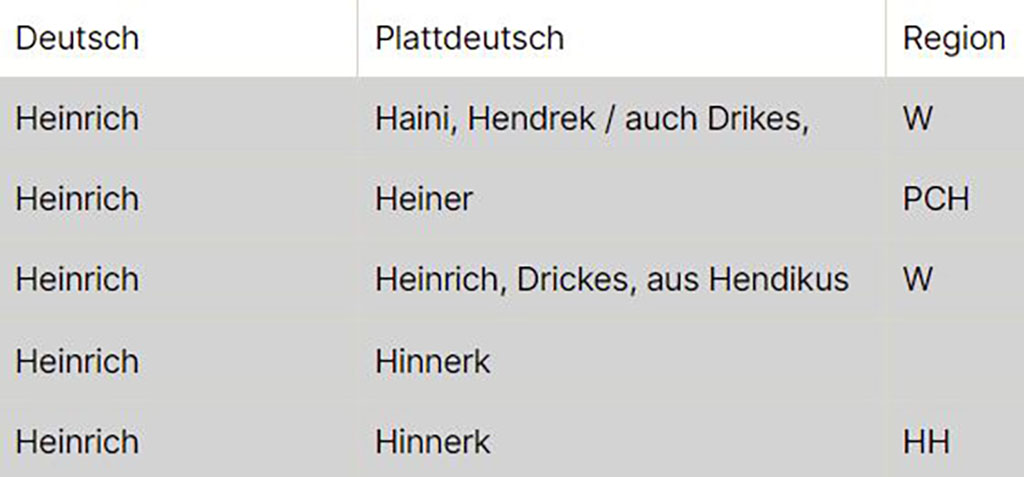

Although Henry and Mary Laker spoke and understood High German or Hochdeutsch, they were also from a region known to speak Low German or Plattdeutsch. In fact, the Laker name itself is Low German.

I found an online Deutsch-Plattdeutsch dictionary and entered the word Pflügen. The results made me rethink my previous theory of a possible phonetic spelling.

Because Low German is not a standardized language, there are several regional spelling variations of the word, but I noticed in particular the entries “ploogen” and “ploögen.”

My next thought of course was to see if the dictionary also had name translations. I entered the name Heinrich.

After seeing the resulting table, I felt more confident that the heinick in Ploogenheinick might have been just another regional variation of Heinrich, and perhaps not a phonetic spelling at all.

One has to wonder if the neighbors had a nickname for the younger Henry as well.

Back to the app

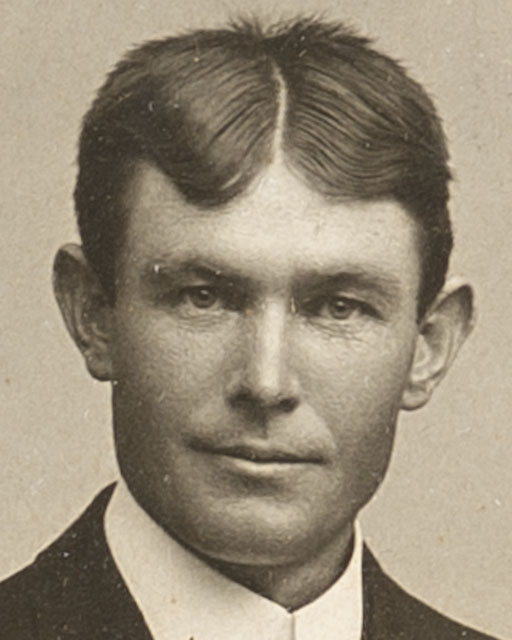

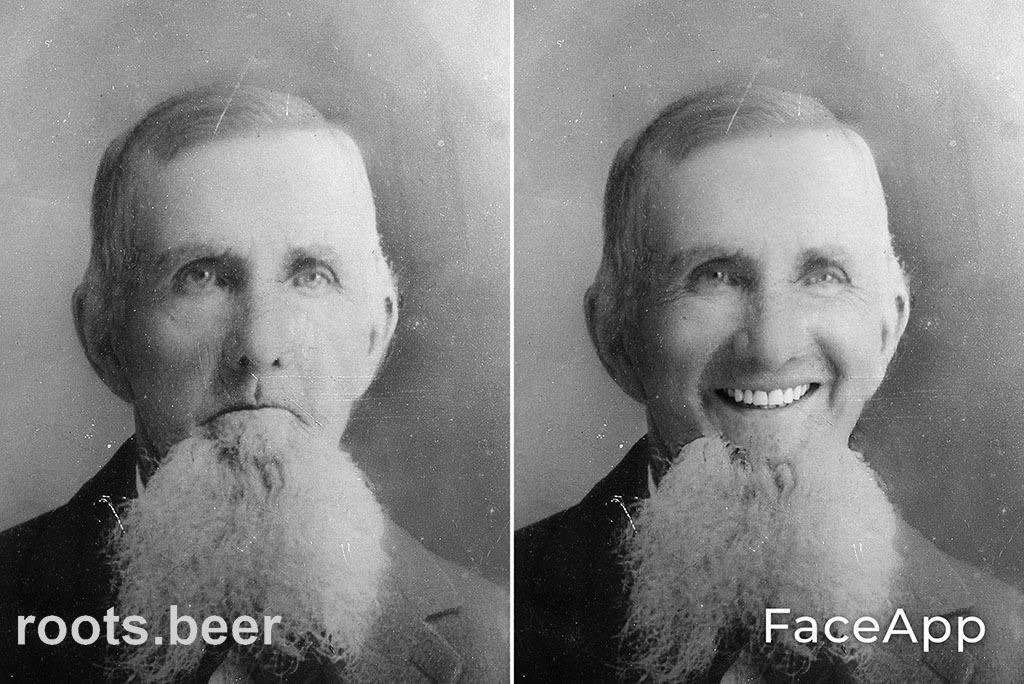

I found the photos of parents Henry and Mary that were dated around the early 1900s. Both were old by then so I wasn’t sure what to expect. I decided first to try using the app to make them look a bit younger and happier. Henry’s results turned out rather well.

Mary, on the other hand, was a different story. The best photo I had of her was taken from farther away and was much grainier. The AI just didn’t really know how to handle it, and the output was the stuff of nightmares.

Both images looked like they could crawl out the screen and grab me, so I decided to just go with the original picture I had of Mary.

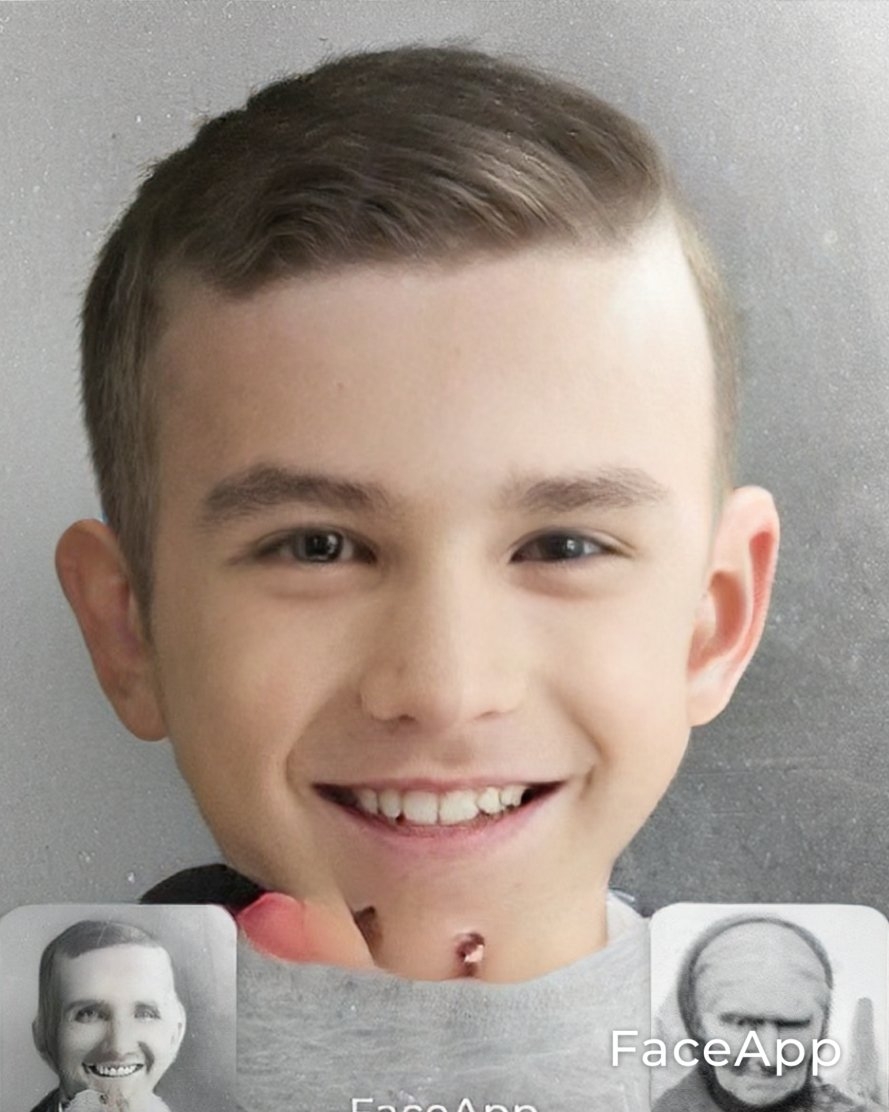

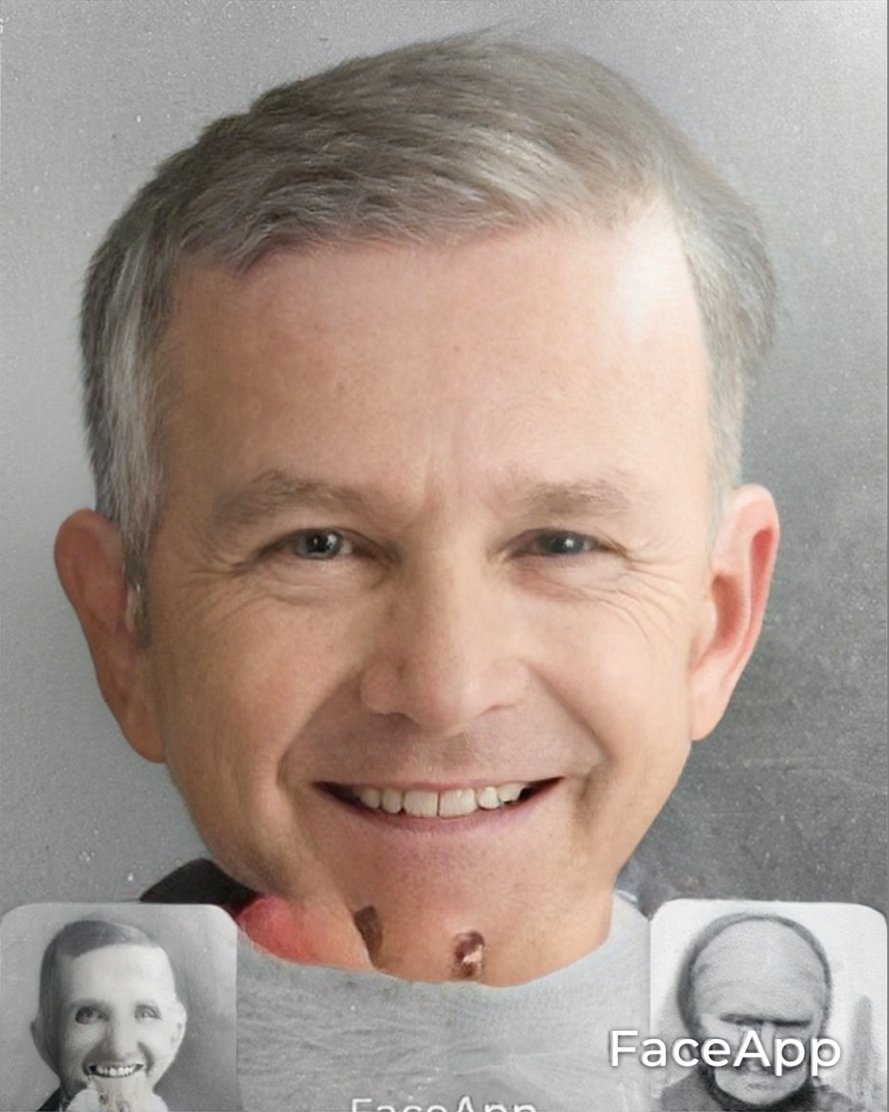

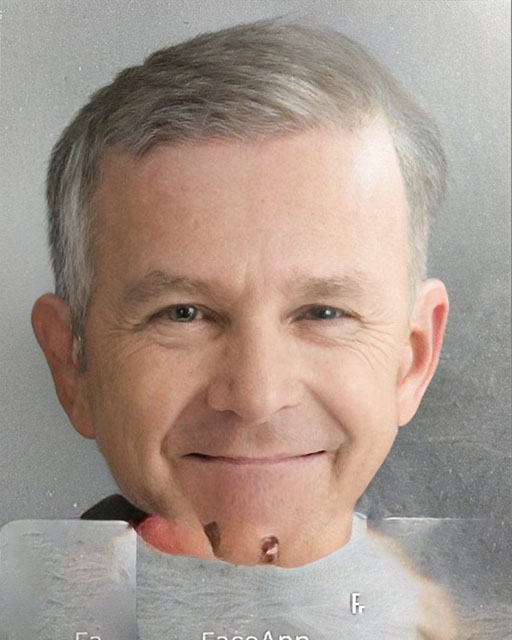

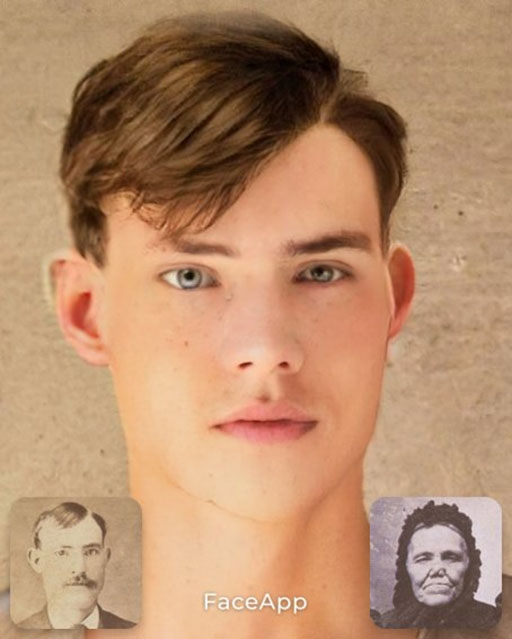

I added them to the app, pressed the “our son” filter and waited for the results. After about five seconds, an image of a young boy appeared on the screen. I saved it and then fed that image back into the app using its age progression feature.

I was impressed by what I saw, especially the picture of the middle-aged man. Henry was 52 at the time of the accident, and this looked to me to be about the right age in the image. The senior Henry’s goatee caused some strange artifacts on the chin, but otherwise the app did a pretty good job considering what I had given it.

The adult AI image looked a lot to me like Joseph, the youngest son of Henry and Mary. I showed Kat a comparison, and she wasn’t sure she saw the similarity.

I thought maybe it was the smile throwing her off, so I opened the image in Photoshop and used a few tools to close his mouth. After that, Kat said she thought the two looked more related.

After I had concluded my experiment, I laughed a little to myself because I realized I hadn’t really proved anything other than that maybe Henry and Mary could have had a son that looked like Joseph — who was their son. FaceApp doesn’t account for the myriad of genealogical traits that parents can pass to a child, and my ancestor could have looked vastly different from what the AI suggested.

I realize this is all a little far-fetched, and comparing this technique to actual forensic reconstruction is quite a stretch. Actual skilled forensic specialists use much more sophisticated tools to solve murders and missing persons cases. FaceApp is little more than a toy.

However, for those of us simply looking to answer burning genealogical questions, this tool provides an interesting and fun option to provide a glimpse at what some of our ancestors may have looked like. If we ever find a real photo of Henry, it will be interesting to revisit this experiment to compare.

Mystery parents

I decided to try another experiment to see if I could solve a mystery on my mother’s side of the family. In this case, I had a picture of my great-grandfather Louis, but the photos we had of his parents Fred and Elizabeth were questionable.

For his father Fred, Mom found an unnamed and undated photo in the attic of her father’s house. She did not have anything to go on other than a feeling that the man bore a striking resemblance to the family. She wrote under the picture “possibly Fred,” but I think she believed with all of her heart that this was Louis’ father. She could feel it.

For Louis’ mother Elizabeth, we received a scanned image of an old woman that was supposedly her, but the details of its origin seemed vague. This picture had not come from our collection, and everything about it felt foreign. The woman in the picture did, however, appear to have a facial feature that is prevalent in the family. (Mental note: Follow up with that relative to learn the photo’s origin.)

So once again I put FaceApp to the test to see if it would produce an “AI son” composite that resembled anything like my great-grandfather Louis.

You be the judge, but I have to say I was stunned by the results. No, it’s not a perfect match, but considering that the photo provided for the mother is an old woman, I’m beyond impressed. Again, there is no way to absolutely prove these are Louis’ parents based on this alone, but on the other hand, I’m feeling maybe a little less skeptical now of Mom’s intuition about Fred and that mysterious photo of Elizabeth. I just can’t help but notice the similarities.

Face-ing the truth

I’m surely not the first person to try this approach, and I wonder how long it will be before FaceApp or another company capitalizes on it. I’d like to challenge these app programmers to teach their Artificial Intelligence one more trick: Reverse the equation and create a “my parents” filter.

In the end, I have to reiterate that this is all just for fun, and it’s not lost on me that maybe my results were dumb luck or that I’m simply seeing similarities because I want to see them.

Being the curious person that I am, I loaded photos of my parents into the app to see if it would conjure up any children that looked like me or one of my siblings. Despite several attempts using multiple photos of Mom and Dad, the app failed to produce any results that looked remotely like us, even though all four of us resemble our parents in various ways.

I guess we just didn’t live up to the app’s expectations.

As I finished writing this, I could almost hear the groans and see the eye rolls coming from some of those who may be more skeptical than myself about this unnatural and peculiar use of FaceApp, but that’s okay.

After all, you know what they say: Opinions are like AI sons — everybody’s got one.

But for the rest of you open-minded souls, I’m curious to hear your thoughts and see your own FaceApp experiments. I will point out that the app is Russian-made which initially caused privacy concerns when it was first launched, but it has since been determined safe.

Just be aware that providing personal information to any app comes with some level of risk.

If you hit the wrong filter, you just might accidentally create your very own Mini-Me.